Activation of Transcription Factor EB Protects Against Proinflammatory Insults Through NF-κB Inhibition in Keratinocytes

Abstract

Keratinocytes are pivotal in mediating cutaneous inflammation. Identifying anti-inflammatory factors within these cells holds promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies to manage skin inflammation. Transcription factor EB (TFEB) has recently emerged as a key regulator linking cellular energy metabolism to inflammatory processes, primarily through its influence on autophagy and NF-κB signaling. However, whether TFEB activation exerts anti-inflammatory effects in keratinocytes remains unclear. In vitro inflammation model was established in HaCat cells by incubation with proinflammatory mediators LPS and IL-1β. Cell viability and TFEB expression and phosphorylation were measured. The effect of TFEB activation by C1 and adenoviral TFEB overexpression on the expression of proinflammatory genes including COX-2, MCP-1 and IL-6 were detected. Also, IκBα protein level were determined. TFEB phosphorylation is increased while TFEB total protein expression is inhibited by treatment with LPS and IL-1β. Pharmacological activation of TFEB by compound C1 and TFEB overexpression suppressed the expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α induced by LPS and IL-1β. TFEB overexpression increased basal IκBα expression and restored IκBα level under LPS treatment. TFEB knockdown reduced TFEB expression and lowered basal expression level of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α. Our findings indicate that TFEB activation can mitigate inflammatory gene expression in keratinocytes triggered by LPS and IL-1β. This implicates TFEB as a significant novel modulator of cutaneous inflammation, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target. Targeting TFEB could thus be a viable strategy for developing new treatments for chronic inflammatory skin conditions.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2026 Yuqin He, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Citation:

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory skin diseases including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (AD) cause impairment of life quality and bring psychological burden to patients 1, 2. Constantly exposed to a variety of environmental stimuli such as pathogenic microbes, UV radiation and mechanical scratch, the keratinocytes perform challenging tasks to integrate external stimuli into intracellular signaling networks to maintain skin homeostasis 3. A healthy state of epidermal keratinocytes with balanced immune response is critical to the overall homeostasis of skin microenvironment.

Keratinocytes play a critical role in initiating cutaneous inflammation by releasing proinflammatory mediators to induce activation of immune cells and microvascular endothelial cells in the dermis and epidermis 4. They also drive disease progression by production of cytokines such as IL-17 to amplify inflammatory response. Therefore, targeting the inflammatory signaling in keratinocytes is likely to bring new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of chronic inflammatory skin diseases 1, 5, 6. Among the many proinflammatory pathways, the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway has a central role in the maintenance of skin epithelial homeostasis through transcriptional induction of proinflammatory genes such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) 3, 7.

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) was recognized as a master regulator of the expression of genes for lysosomal biogenesis 8. TFEB activation enhances autophagic flux by linking autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis 8. Interestingly, recent studies showed that TFEB plays an important role in regulation of inflammatory response in several cell types, including vascular endothelial cells and macrophages 9, 10, 11. TFEB exerts its anti-inflammatory effect mainly through enhancement of antioxidant defense and inhibition of NF-κB pathway 12, 13. However, whether TFEB is expressed in keratinocytes is unclear and whether TFEB activation can produce an anti-inflammatory effect in keratinocytes remains unknown.

In the present study, we hypothesize TFEB inhibits inflammation in keratinocytes and TFEB is a novel regulator of proinflammatory gene expression in response to proinflammatory stimuli. Our data show that TFEB expression and activity are inhibited by cytokine interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in keratinocytes, and TFEB activation by pharmacological agent C1 as well as TFEB overexpression produces anti-inflammatory effect likely through increasing IκBα protein level.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Antibodies

HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (Biotechnology, A0208), HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (Biotechnology, A0216), GAPDH Monoclonal antibody (Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig), Anti-MCP-1 antibody (Abcam, ab9669), TFEB Polyclonal antibody (Proteintech, 13372-1-AP), Phospho-TFEB (Ser211) (E9S8N) Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, 37681), Anti-COX2 / Cyclooxygenase 2 (EPR12012) (Abcam, ab179800), IκBα (L35A5) Mouse mAb (Amino-terminal Antigen) (Cell Signaling Technology, 4814), Lipopolysaccharide (Merck, 297-473-0), IL-1β (Minneapolis, 201-LB-010), DMEM (BI, 06-1055-57-1ACS), PBS (Gibco, 14190144C), 0.25 % Trypsin-EDTA (Adamas life, C8019-100mL), Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco, 10099141C), Dermal Cell Basal Medium (ATCC, PCS-200-030), Keratinocyte Growth Kit (ATCC, PCS-200-040), Trypsin-EDTA for Primary Cells (ATCC, PCS-999-003), Trypsin Neutralizing Solution (ATCC, PCS-999-004), RIPA lysis buffer (Biotechnology, P0013C), PhosSTOP EASYpack (PhosSTOP™) (Sigma, 4906845001), Lipo8000 (Biotechnology, C0533), CCK-8 cell proliferation detection kit (Share-bio, SB-cck8m). Adenoviral TFEB vector (Ad-TFEB) was kindly provided by SHANGHAI GENECHEM.

Cell Culture

Human immortalized keratinocytes HaCaT were from Meisen (CTCC-002-0012) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, placed in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37℃. Human Primary Epidermal Keratinocytes from Neonatal Foreskin (HEKn) from ATCC (PCS-200-010) were cultured in Dermal Cell Basal Media supplemented with Keratinocyte Growth Kit components (Bovine Pituitary Extract, Final concentration 0.4%; rh TGF-α, Final concentration 0.5 ng/mL; L-Glutamine, Final concentration 6 mM; Hydrocortisone Hemisuccinate, Final concentration 100 ng/mL; rh Insulin, Final concentration 5 mg/mL; Epinephrine, Final concentration 1.0 mM; Apo-Transferrin, Final concentration 5 mg/mL).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Samples were homogenized in RNA-easy Isolation Reagent RNA (Vazyme, R701-01), total RNA was isolated and extracted, and 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed with gDNA Eraser (Takara, RR047A) to synthesize cDNA. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on the QuantStudioTM3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the Chamq Sybr Color QPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q441-03), GAPDH was used as internal control, and gene expression was analyzed by ΔΔCT method. The primer sequence is as follows:

GAPDH (CCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC, ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCA),

MCP-1 (CAGCCAGATGCAATCAATGCC, TGGAATCCTGAACCCACTTCT),

TNF-α (CCTCTCTCTAATCAGCCCTCTG, GAGGACCTGGGAGTAGATGAG),

COX-2 (ATGCTGACTATGGCTACAAAAGC, TCGGGCAATCATCAGGCAC),

TFEB (GCCATCAATACCCCCGTCC,AGGACTGCACCTTCAACACC).

Western Blotting

The cells were homogenized in a lysis buffer composed of RIPA buffer and phosphatase inhibitor, the protein lysate was collected, centrifuged at 4℃ and 12 000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was taken for protein assay by BCA method. The protein samples were mixed with loading buffer, boiled at 100℃ for 5 min, and then loaded into acrylamide gel. The protein was separated by electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membrane. The PVDF membrane was blocked with 3% BSA containing Tween-20 Tris buffer saline for 30 min. The primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4℃. The next day, PVDF membrane was washed three times in Tris buffer saline containing Tween 20 and then incubated with the secondary antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase at room temperature for 1 hour. The PVDF membrane was washed in Tris buffer saline containing Tween 20 for three times and then developed by chemiluminescence detection. The detection instrument was an integrated chemiluminescence fluorescence gel imaging analysis system (Beijing Saizhi Venture Technology Co., Ltd., Smartchemi 610 plus).

shRNA-mediated TFEB knockdown

Sequence (GATGTCATTGACAACATTA) targeting human TFEB mRNA was cloned to PLKO.1 lentiviral vector and packaged to generate lentivirus in HEK293T cells. HaCat cells were transduced with lentivirus TFEB-shRNA at MOI 20, and the medium was changed 12 hours post-transduction. 72 hours post-transduction, cell samples were collected, and the expression of TFEB was detected and the effect of TFEB knockdown on proinflammatory gene expression was determined after LPS and IL-1β stimulation.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were inoculated in 96-well plates with 10000 cells per well. The next day, TFEB Activator C1 at 10 μM was added to treat the cells for different durations. At the end of treatment, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added into each well for 1 h incubation. Then, the incubated cell culture plate was placed on a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy LX Multi-Mode), and the absorbance was detected at 450 nm. Cell survival rate = (OD value of observation group-OD value of blank group)/(OD value of control group-OD value of blank group).

Statistical Analysis

The data was expressed as mean ± SEM, and the data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. GAPDH is the internal control of gene and protein expression. Student’s t-test was used to analyze the differences between the two groups, and two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the differences between multiple groups. p< 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Results

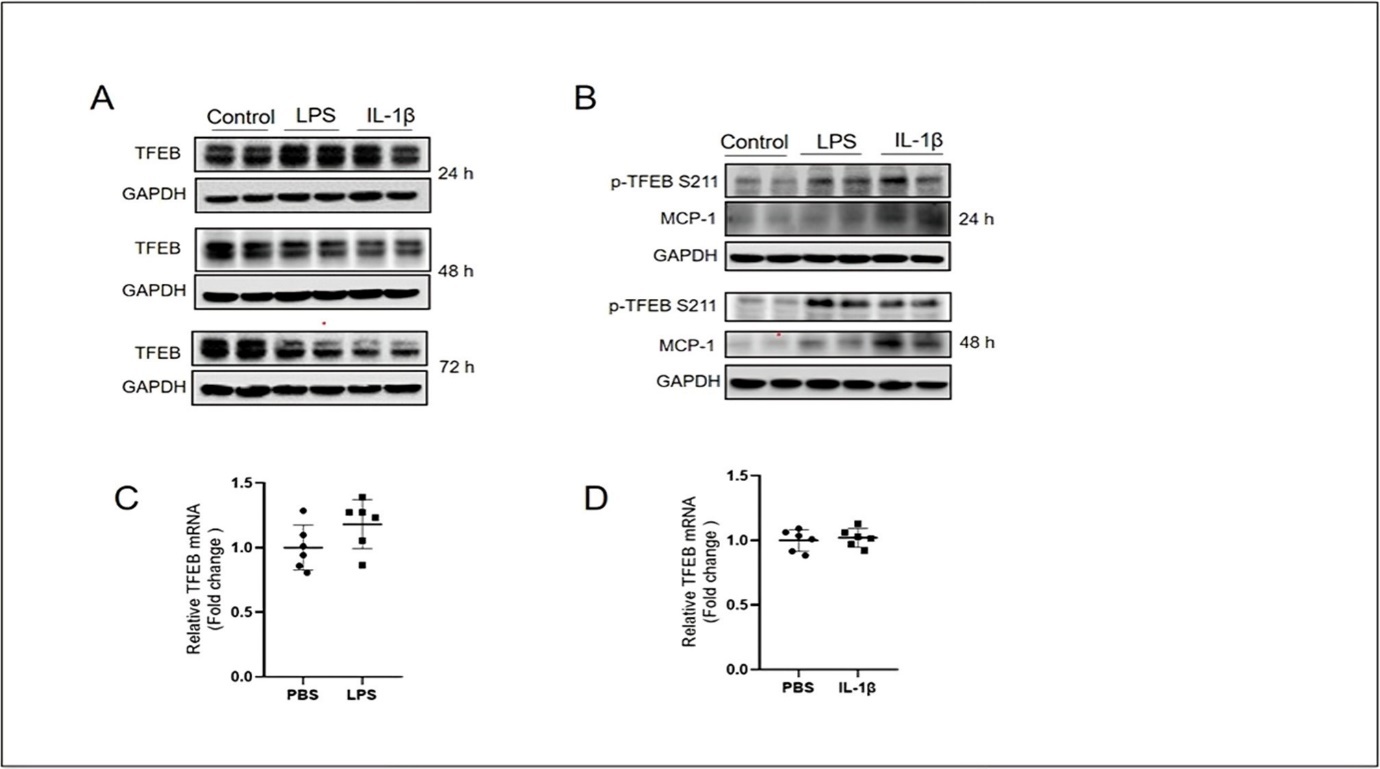

Proinflammatory factors reduce TFEB activity in keratinocytes

To investigate a potential role of TFEB in modulating proinflammatory responses in the skin, we first tested whether LPS and IL-1β stimulation affects TFEB protein level in HaCaT cells, which are the immortalized human keratinocytes. Western blotting results showed that a reduced expression of TFEB protein at 48 h after treatment with LPS and IL-1β, and this reduction become more obvious after treatment with LPS and IL-1β for 72 h (Figure 1A). As TFEB activity is critically modulated by the phosphorylation, we next determined its phosphorylated level in HaCaT cells. We found that, together with an elevated MCP-1 protein expression, exposure to LPS and IL-1β for 24 and 48 h significantly increased phosphorylated TFEB level at serine 211 (p-TFEB S211) (Figure 1B), indicating increased cytosolic retention of TFEB under treatment with these proinflammatory mediators. Real-time quantitative PCR results showed that TFEB mRNA did not change after treatment with LPS and IL-1β (Figure 1C and D). Taken together, these data suggest TFEB is likely to play an anti-inflammatory role during the response to proinflammatory stimuli in keratinocytes.

Figure 1.Keratinocytes stimulated with proinflammatory mediators show a decreased TFEB activity. (A) Western blotting results showing the protein expression level of TFEB in HaCaT cells stimulated with LPS (10 μg/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 24, 48 and 72 h. (B) Western blotting results showing the protein expression level of p-TFEB S211 and MCP-1 in HaCaT cells stimulated with LPS (10 μg/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 24 and 48 h. (C) Quantitative PCR results showing the mRNA expression level of TFEB in HaCaT cells stimulated with LPS (10 μg/mL). (D) Quantitative PCR results showing the mRNA expression level of TFEB in HaCaT cells stimulated with IL-1β (10 ng/mL).

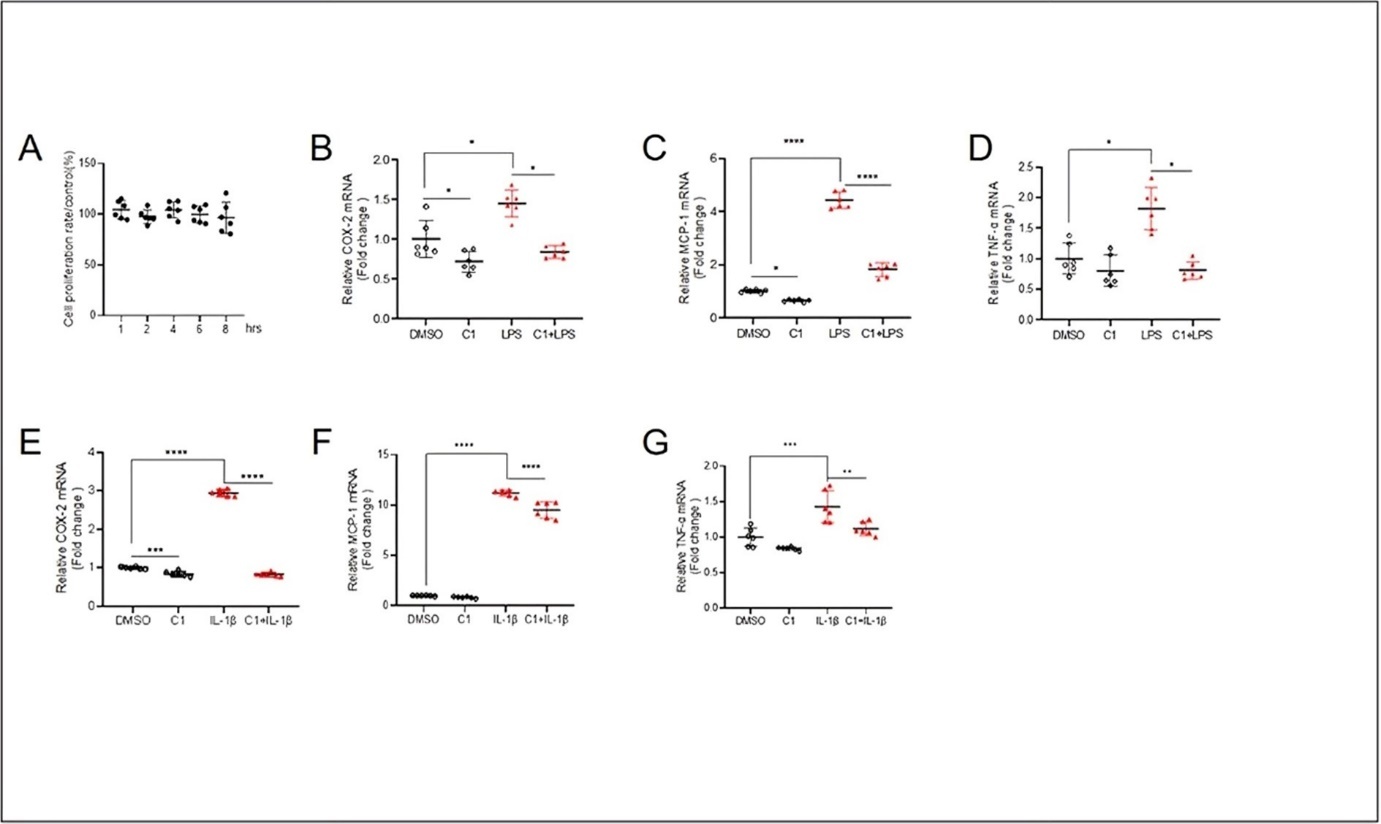

Activation of TFEB inhibits the expression of proinflammatory factors in keratinocytes

TFEB activity can be pharmacologically increased by its activator C1. We first treated HaCaT cells with C1 for different durations and determined its effect on cell proliferation. The results showed C1 at 10 μM did not affect the proliferation of HaCaT cells during the treatment durations (Figure 2A). To investigate whether TFEB holds anti-inflammatory effect in the keratinocytes, we detected the expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α, which are critical proinflammatory factors, in C1-treated HaCaT cells after exposure to LPS. We showed that LPS upregulated the expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α genes in HaCaT cells (Figure 2B-D). Pre-treatment with TFEB activator C1 for 4 h reversed LPS-induced expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α (Figure 2B-D). We tested the effect of C1 in IL-1β-induced inflammation and found that while C1 only partially reduced IL-1β-induced COX-2 and MCP-1 expression, it effectively suppressed TNF-α expression induced by IL-1β (Figure 2E-G). These results demonstrate that pharmacological activation of TFEB has anti-inflammatory function in keratinocytes.

Figure 2.TFEB activation by C1 inhibits COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α mRNA levels induced by LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes. The cell proliferation rate (A) of HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8h. Quantitative PCR results showing the LPS- (10 μg/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (B), MCP-1 (C) and TNF-α (D) in HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4h. Quantitative PCR results showing the IL-1β- (10 ng/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (E), MCP-1 (F) and TNF-α (G) in HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4 h. Data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P< 0.001,****P<0.0001.

Figure 2. TFEB activation by C1 inhibits COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α mRNA levels induced by LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes. The cell proliferation rate (A) of HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8h. Quantitative PCR results showing the LPS- (10 μg/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (B), MCP-1 (C) and TNF-α (D) in HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4h. Quantitative PCR results showing the IL-1β- (10 ng/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (E), MCP-1 (F) and TNF-α (G) in HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4 h. Data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P< 0.001,****P<0.0001.

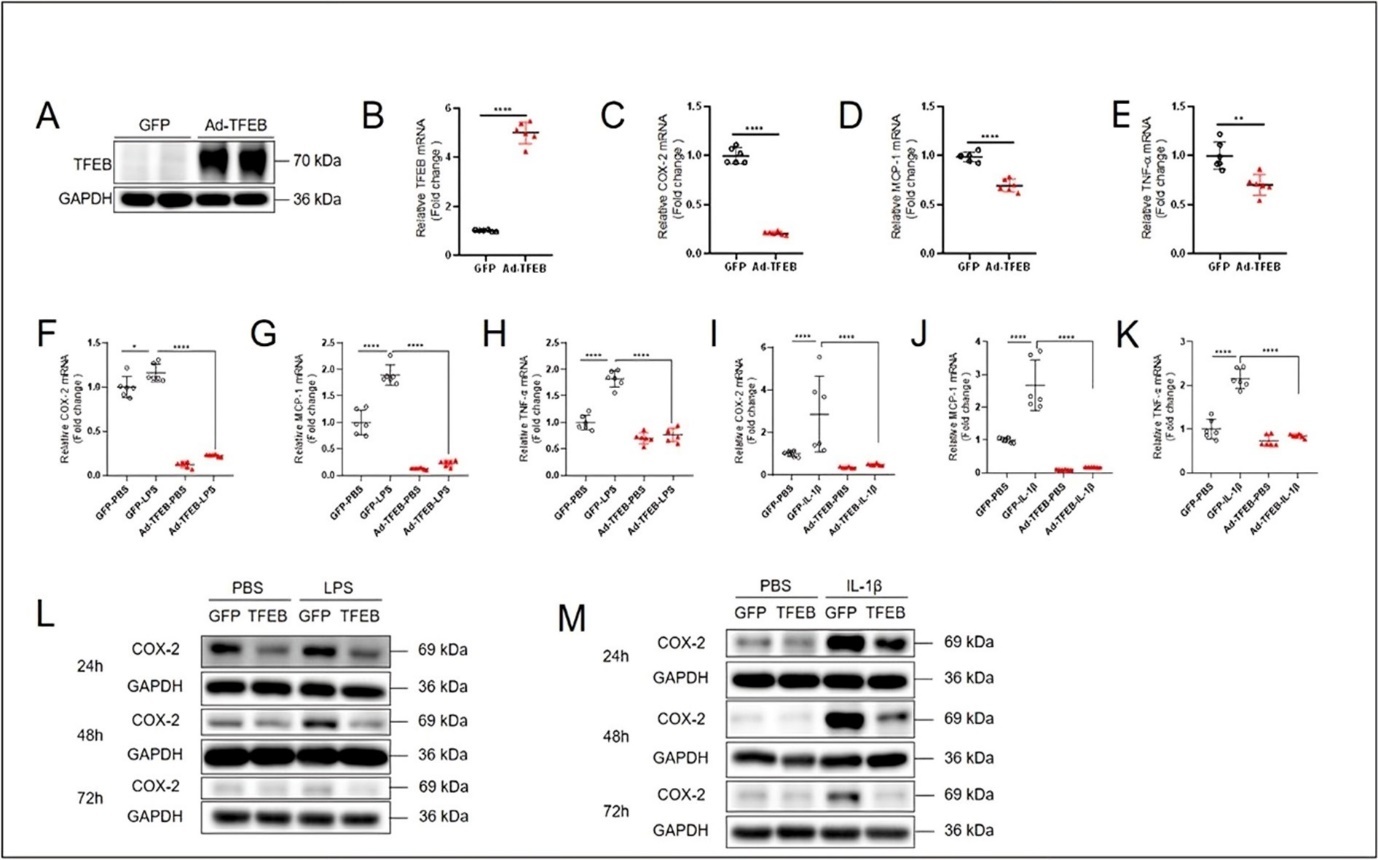

Overexpression of TFEB inhibits the elevation of proinflammatory factors by LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes

To investigate whether TFEB is a component of the anti-inflammatory defense system in keratinocytes, we made effort to overexpress TFEB. The effect of overexpression of TFEB was determined. Western blotting and Real-time quantitative PCR results showed an increased expression of TFEB protein and mRNA (Figure 3A and B). To examine whether TFEB plays a role in regulation of the basal expression of proinflammatory genes, we detected mRNA levels of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α. The qPCR results showed that the mRNA levels of these genes were decreased in TFEB-overexpressing HaCaT Cells (Figure 3C-E). Importantly, after TFEB was successfully overexpressed, HaCaT cells were stimulated with LPS (10 μg/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. Compared with those in the GFP group, the gene expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α mRNA was all increased in GFP-LPS group. Consistently, LPS- and IL-1β-induced mRNA expression of COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α was all brought down by Ad-TFEB overexpression (Figure 3F-K). Because COX-2 is a critical proinflammatory enzyme, we determined its protein expression in keratinocytes exposed to LPS and IL-1β. Western blotting results showed that a significantly increased COX-2 expression by LPS- and IL-1β-induced HaCaT Cells for 24, 48 and 72 h, and Ad-TFEB treatment not only suppressed basal and also induced COX-2 expression under these conditions (Figure 3L and M). Taken together, these results demonstrate that increasing TFEB expression is beneficial against proinflammatory insults in keratinocytes.

Figure 3.Overexpression of TFEB inhibits COX-2, MCP-1and TNF-α mRNA levels induced by LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes. The results of western blotting (A) and quantitative PCR (B) showed that Ad-TFEB successfully increased TFEB expression. Quantitative PCR results showing the changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (C), MCP-1 (D) and TNF-α (E) in HaCaT cells treated with Ad-TFEB for 24 h. Quantitative PCR results showing the LPS- (10 μg/mL, 4 h) and IL-1β- (10 ng/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of COX-2 (F and I), MCP-1 (G and J) and TNF-α (H and K) in HaCaT cells pretreated with Ad-TFEB for 24 h. (L and M) Western blotting results showing the protein expression level of COX-2 in Ad-TFEB pretreated HaCaT cells stimulated with LPS and IL-1β for 24, 48 and 72h. Data was analyzed using unpaired t-test or two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P< 0.001,****P<0.0001.

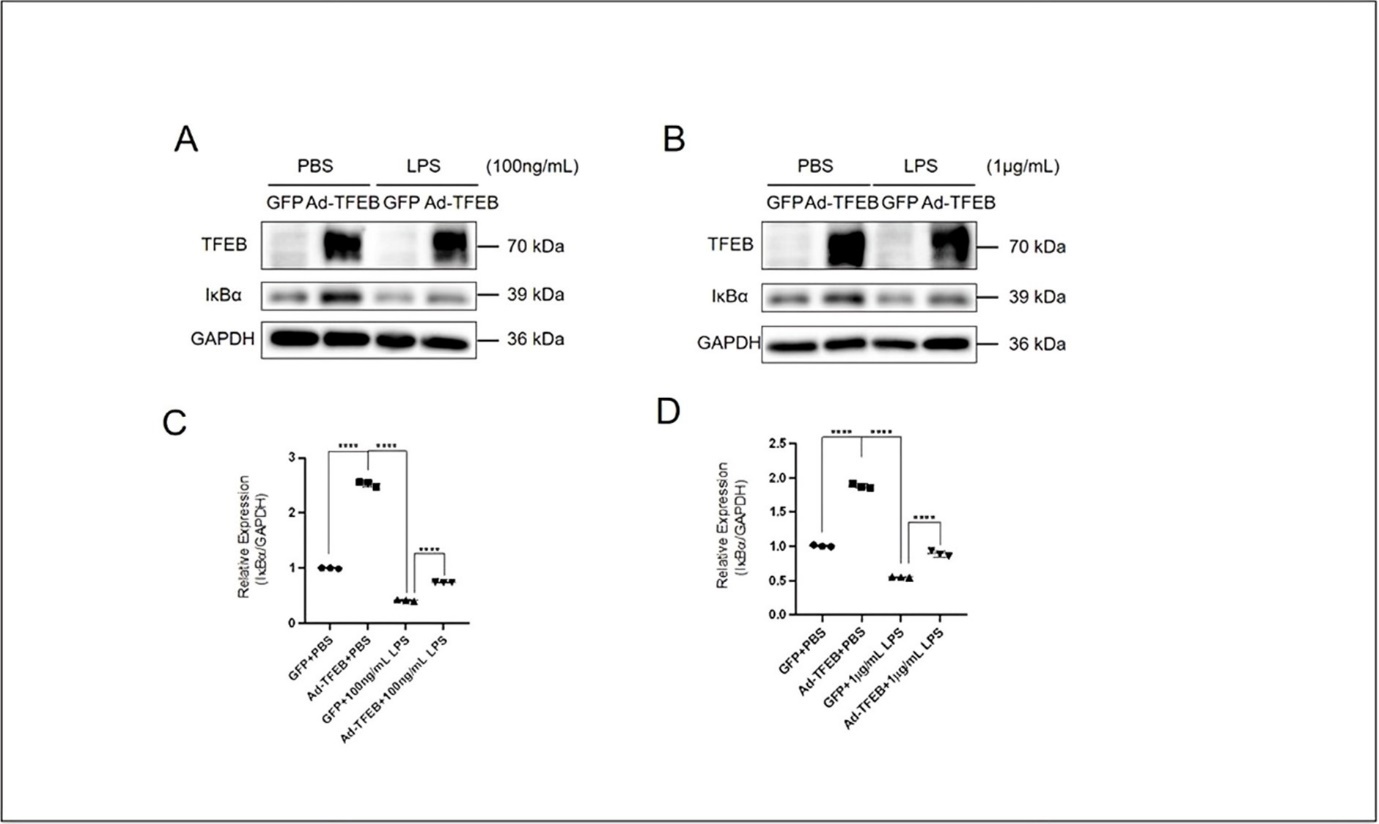

TFEB restores the expression of IκBα

To investigate the anti-inflammatory mechanism of TFEB in keratinocytes, we examined whether TFEB plays a role in regulation of the activity of NF-κB pathway, the master regulator of cellular inflammatory response. We detected the protein expression of IκBα, a crucial inhibitory protein of NF-κB. Western blotting and Image J analyzing results showed that a significantly decreased IκBα expression by treatment with different concentrations of LPS (100 ng/mL and 1 μg/mL) for 30 min in HaCaT Cells (Figure 4A-D), and Ad-TFEB overexpression dampened the effect of LPS on IκBα expression under these conditions (Figure 4A-D). These results indicate that activation of TFEB in keratinocytes promotes the expression of IκBα, thus inhibiting the activation of NF-κB to achieve anti-inflammatory effect.

Figure 4.TFEB restores the expression of IκBα. (A) Western blotting results showing the LPS- (100 ng/mL, 30 min) induced changes of protein expression levels of TFEB and IκBα in HaCaT cells pretreated with Ad-TFEB for 24 h. (B) Western blotting results showing the LPS- (1 μg/mL, 30 min) induced changes of protein expression levels of TFEB and IκBα in HaCaT cells pretreated with Ad-TFEB for 24 h. Summarized western blotting results were analyzed using Image J to show the level of IκBα exposed to (C) LPS- (100 ng/mL, 30 min) and (D) LPS- (1 μg/mL, 30 min). Data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA, *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P< 0.001,****P<0.0001.

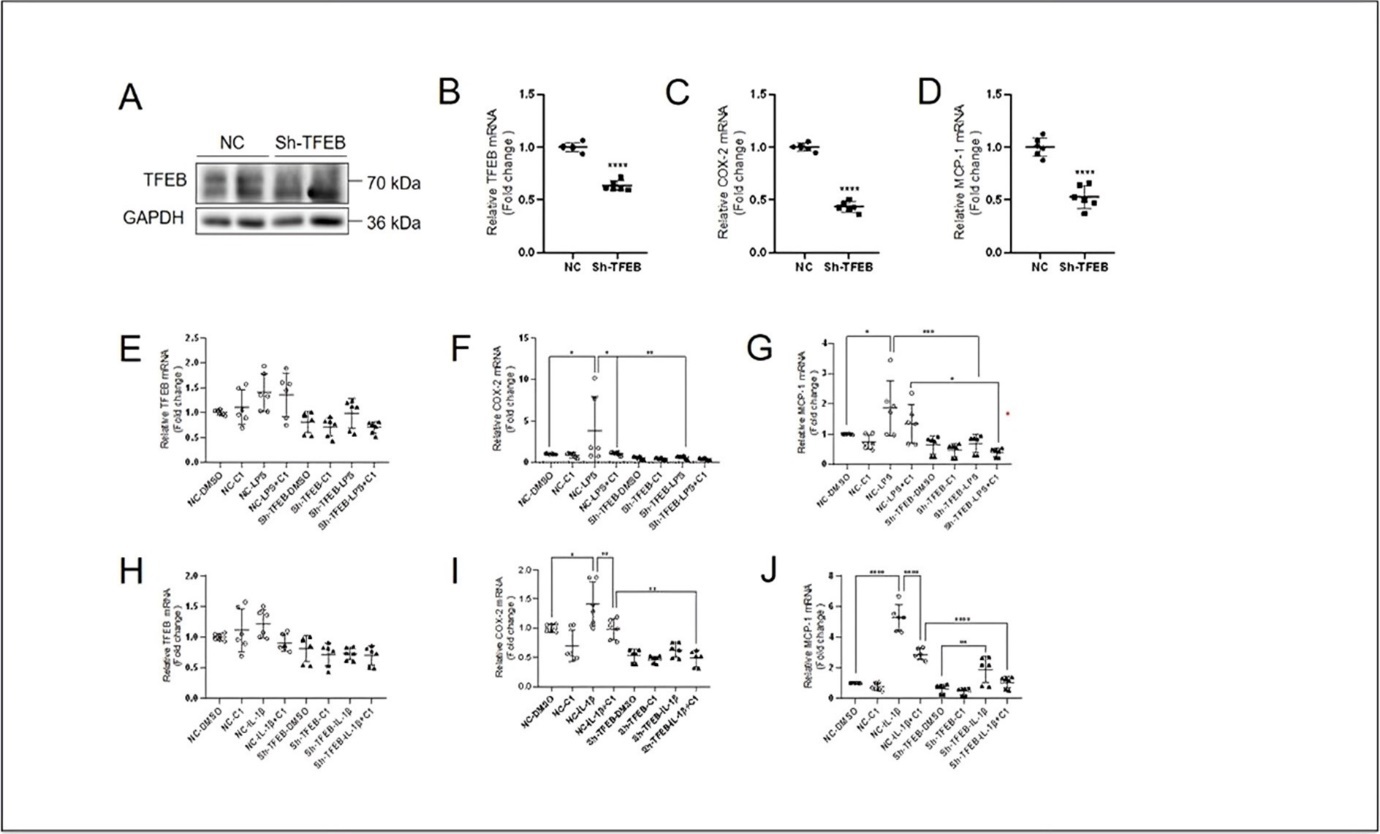

TFEB is required for basal expression of proinflammatory genes

To investigate whether TFEB is required for the basal anti-inflammatory activity in keratinocytes, we knocked down TFEB using shRNAs. The effect of TFEB knockdown was firstly determined. Western blotting and Real-time quantitative PCR results showed that a decreased expression of TFEB (Figure 5A and B). To examine whether basal TFEB expression plays a role in regulation of the expression of proinflammatory genes, we detected mRNA levels of COX-2 and MCP-1. The qPCR results showed that the mRNA levels of COX-2 and MCP-1 was decreased in Sh-TFEB treated HaCaT Cells (Figure 5C and D). We detected the effect of C1 on expression of TFEB (Figure 5E and H), COX-2 (Figure 5F and I) and MCP-1 (Figure 5G and J) in Sh-TFEB treated HaCaT cells after exposure to LPS (10 μg/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. The qPCR results showed that TFEB-dependent inhibitory effect on the expression of COX-2 and MCP-1 was not changed, indicating that TFEB is required for the basal and stimulated expression of pro-inflammatory genes.

Figure 5.Reduced TFEB expression in keratinocytes by TFEB shRNA. The results of western blotting (A) and quantitative PCR (B) showed that TFEB shRNA successfully knocked down TFEB expression. The quantitative PCR results showed that changed mRNA levels of COX-2 (C) and MCP-1 (D) after TFEB was knocked down. Quantitative PCR results showing the LPS- (10 μg/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of TFEB (E), COX-2 (F) and MCP-1 (G) in basal and Sh-TFEB HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4 h. Quantitative PCR results showing the IL-1β- (10 ng/mL, 4 h) induced changes of mRNA levels of TFEB (H), COX-2 (I) and MCP-1 (J) in basal and Sh-TFEB-treated HaCaT cells pretreated with TFEB activator C1 (10 μM) for 4 h. Data was analyzed by unpaired t-test, * indicates the result compared with NC, *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P <0.001,****P<0.0001.

Discussion

In the present study, we observed that TFEB expression and activity are suppressed by proinflammatory mediators LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes. Pharmacological activation of TFEB by compound C1 and adenoviral TFEB overexpression inhibit the expression of proinflammatory genes including COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α induced by LPS and IL-1β. TFEB overexpression potentiates IκBα expression level under LPS treatment, indicating that TFEB likely inhibits NF-κB to achieve anti-inflammatory effect. Knockdown of TFEB by shRNA decreased the mRNA levels of COX-2 and MCP-1, indicating that TFEB expression is involved in regulation of basal level of proinflammatory gene expression.

An interesting observation in the present study is that TFEB phosphorylation at serine 211 (p-TFEB S211) is increased by treatment with LPS and IL-1β for different durations. p-TFEB S211 is regulated by mTORC1 under normal growth conditions and increased level of p-TFEB S211 indicates TFEB cytosolic retention and degradation 14, 15. Our data showing decreased TFEB total protein level accompanied with increased phosphorylated-TFEB level at serine 211 suggest there are similar mechanisms existing in the regulation of TFEB activity by mTORC1 in keratinocytes. However, it is unclear whether inhibition of mTORC1 can reverse the effect of LPS and IL-1β on TFEB expression and activity. Future investigation on skin inflammation using mTORC1 inhibitors such as rapamycin should reveal the mechanistic connection of TFEB with epidermal homeostasis.

The compound C1 was identified as a novel curcumin analog which can bind to and activate TFEB without inhibition of mTORC1 16. We used C1 to activate TFEB in keratinocytes and found that C1 treatment effectively suppressed the expression of proinflammatory genes induced by LPS and IL-1β, suggesting C1 holds the potential in combating against skin inflammation. As an orally effective synthetic compound, C1 can enhance autophagy through promoting TFEB nuclear localization. Recently, C1 was shown to protect against sensory hair cell injury and delay age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice through promoting TFEB activity and autophagy 17. The effect of C1 in pro-inflammatory skin disorders remains unknown. It is worth to investigate whether local delivery of C1 has an anti-inflammatory effect in skin disorders.

We also used genetic methods to overexpress TFEB, detecting that Ad-TFEB inhibits the expression of proinflammatory genes including COX-2, MCP-1 and TNF-α induced by LPS and IL-1β in keratinocytes. COX-2 is a well-known mediator of pro-inflammatory processes in skin 7, and COX-2 specific inhibitors are beneficial in reducing cutaneous inflammation by decreasing edema and vascular permeability 18, 19. Interestingly, curcumin was found to inhibit COX-2 expression in keratinocytes exposed to UVB irradiation 20. It will be intriguing to study whether C1 can inhibits COX-2 expression through TFEB in UVB-irradiated keratinocytes.

IκBα is the most common member of the IκB protein family, and its primary function is to inhibit the activity of NF-κB 21. NF-κB is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of many genes, including those related to inflammation, immune response, and apoptosis. Our data showed that a significantly decreased expression of IκBα by treatment with different concentrations of LPS in HaCaT Cells, and Ad-TFEB overexpression dampened the effect of LPS on IκBα expression under these conditions. This data indicates that activation of TFEB in keratinocytes promotes the expression of IκBα, thus inhibiting the activation of NF-κB to achieve anti-inflammatory effect.

In addition to being regulated by NF-κB, the expression of MCP-1, TNF-α and COX-2 is also regulated by AP-1 transcription factors and COX-2 in some cases is mainly regulated by AP-1 22, 23. Our data showed that, under TFEB knockdown condition, basal and LPS-induced expression of COX-2 and MCP-1 is attenuated, suggesting TFEB is required for the transcription of basal level of COX-2 and MCP-1 in keratinocyte. It is likely that, in keratinocytes, TFEB also regulates AP-1 activity, which also contributes to COX-2 and MCP-1 expression. Crosstalk between AP-1 and NF-κB signaling was reported 24. We speculate that, when TFEB expression is suppressed in keratinocytes, basal AP-1 activity is reduced to downregulate COX-2 and MCP-1 expression. This speculation explains that although the anti-inflammatory function of C1 remains effective, why reduced expression of COX-2 and MCP-1 is observed when exposure to LPS and IL-1β in TFEB-silenced keratinocytes. Further study interrogating the regulation of AP-1 activity by TFEB is highly likely to obtain evidence.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study shows a novel role of TFEB in the maintenance of pro-inflammatory signaling in keratinocytes. TFEB activation is likely a promising approach to alleviate inflammation in the skin.

Author contribution

YS and YH drafted the manuscript; YH and YS performed the experiments; HX analyzed the data and contributed to the revision of manuscript; HX designed the study. All authors have read and give approval to the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the internal fund from Zhejiang eSerch Pharmaceutical Technology (YSQYF2022A01).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is based on the cell line and our laboratory has BSL 2 certificate and therefore no formal ethics approval was required for this study.

References

- 1.Zhou X, Chen Y, Cui L, Shi Y, Guo C. (2022) Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: from keratinocyte perspective.Cell Death Dis.13.

- 2.Esche C, A de Benedetto, L A Beck. (2004) Keratinocytes in atopic dermatitis: inflammatory signals.Curr Allergy Asthma Rep.4.

- 3.Wullaert A, M C Bonnet, Pasparakis M. (2011) NF-κB in the regulation of epithelial homeostasis and inflammation.Cell Res.21.

- 4.J N Barker, R S Mitra, C E Griffiths, V M Dixit, B J Nickoloff. (1991) Keratinocytes as initiators of inflammation.Lancet.337. 211-214.

- 5.S L. (2023) Keratinocytes and immune cells in the epidermis are key drivers of inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa providing a rationale for novel topical therapies.Br JDermatol.188. 407-419.

- 6.L D Meesters. (2023) Keratinocyte signaling in atopic dermatitis: investigations in organotypic skin models towards clinical application.J Allergy Clin Immunol.

- 7.Liana D, Eurtivong C, Phanumartwiwath A. (2024) Boesenbergia rotunda and Its Pinostrobin for Atopic Dermatitis:. Dual 5-Lipoxygenase and Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitor and Its Mechanistic Study through Steady-State Kinetics and Molecular Modeling.Antioxidants (Basel).13 74.

- 9.J E Irazoqui. (2020) Key Roles of MiT Transcription Factors. in Innate Immunity and Inflammation.Trends Immunol.41 157-171.

- 10.O A Brady, J A Martina, Puertollano R. (2018) Emerging roles for TFEB in the immune response and inflammation.Autophagy.14.

- 11.Emanuel R. (2014) Induction of lysosomal biogenesis in atherosclerotic macrophages can rescue lipid-induced lysosomal dysfunction and downstream sequelae.Arterioscler.Thromb.Vasc. , Biol.34

- 12.Song W. (2019) . Endothelial TFEB (Transcription Factor EB) Restrains IKK (IκB Kinase)-p65 Pathway to Attenuate Vascular Inflammation in Diabetic db/db Mice.Arterioscler.Thromb.Vasc. Biol.39 .

- 13.Lu H. (2017) TFEB inhibits endothelial cell inflammation and reduces atherosclerosis.Sci Signal.10.

- 14.J A Martina, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R. (2012) MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB.Autophagy.8. 903-914.

- 15.Napolitano G. (2018) mTOR-dependent phosphorylation controls TFEB nuclear export.Nat. Commun.9 3312-10.

- 16.Song J-X. (2016) A novel curcumin analog binds to and activates TFEB in vitro and in vivo independent of MTOR inhibition.Autophagy.12. 1372-1389.

- 17.He W. (2023) Promoting TFEB nuclear localization with curcumin analog C1 attenuates sensory hair cell injury and delays age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice.Neurotoxicology.95. 218-231.

- 18.J L Lee, Mukhtar H, D R Bickers, Kopelovich L, Athar M. (2003) Cyclooxygenases in the skin: pharmacological and toxicological implications.ToxicolApplPharmacol.192. 294-306.

- 19.Moon H, A C White, A D Borowsky. (2020) New insights into the functions of. Cox-2 in skin and esophageal malignancies.Exp Mol Med.52 .

- 20.Cho J-W. (2005) Curcumin inhibits the expression of COX-2 in UVB-irradiated human keratinocytes (HaCaT) by inhibiting activation of AP-1: p38 MAP kinase and JNK as potential upstream targets.Exp Mol Med.37.

- 21.Song W. (2019) . Endothelial TFEB (Transcription Factor EB) Restrains IKK (IκB Kinase)-p65 Pathway to Attenuate Vascular Inflammation in Diabetic db/db Mice.Arterioscler.Thromb.Vasc. Biol.39 .

- 22.Kim S-H. (2009) Involvement of NF-kappaB and AP-1 in COX-2 upregulation by human papillomavirus 16 E5 oncoprotein.Carcinogenesis.30. 753-757.